Overview

The project’s aim is to foster resilient learning environments, lessen early school leaving, and give European children (ages 4 -6) a good start in their education while providing and advancing technical skills in working with technology that will serve them well in life. For this purpose, the partnership has developed age appropriate ICT animation tools and games - as well as pedagogical framework specific to the transition phase from kindergarten to school.

Recommendation

Francesca Dagnino and Niccolò de Salvo (ITD-CNR)

In the light of the literature reporting about the effects of the covid pandemic on ECEC and of the interviews carried out with informants we developed the following recommendations:

-

Prioritize in-person attendance: Firstly, priority should be given to in-person attendance for

children in this age group. As was widely discussed in the literature, the abrupt interruption

of kindergarten attendance, although needed, negatively impacted on cognitive and socio-

emotional development of children and particularly of the most disadvantaged (see for

example La Valle et al., 2022 and UNESCO, 2020). Students under six years old have difficulty

maintaining attention and engagement for long periods of time, which can make distance

learning challenging. Additionally, children in this age group require significant social

interactions and structured learning environments that cannot be ensured in remote

education.

-

Ensure technological support and financial accessibility for distance learning: the

experience with the pandemic showed the inequalities in terms of access to digital

technologies (both infrastructure and equipment) and how they can lead to the exclusion of

some groups of children in the case of a need for distance learning (Carretero-Gomez, et al,

2021). To contrast the increase of inequalities due to the different opportunities,

governments should provide the necessary technological support to children and their

families. In particular, governments should support those who cannot afford the cost of

computer devices and reliable internet connections. This could include the provision of free

or low-cost computer devices and internet connections for low-income families.

-

Provide support for parents: During the pandemic parents found themselves significantly

involved in the educational activities of their children (Benigno et al., 2020), and they were

not always ‘equipped’ to answer to the schools requests. Parents should be supported in

helping their children participate in distance learning (and in general in dealing with ICTs) by

providing them with the necessary information and resources to fulfill their role effectively

(Carretero-Gomez, et al, 2021). Schools may set up online meetings both to share

educational objectives and strategies and to familiarize parents with ICTs adopted with their

children.

-

Ensure communication between the school and parents: school-parents communication is

paramount to allow a fruitful collaboration. It is necessary to maintain regular

communications (through phone calls, mails, chat, online individual/group meetings) with

parents, providing updates on the progress of the school and suggestions for helping

children learn at home.

-

Attention to setting during online lessons: It is necessary to ensure that children have

access to a safe and secure environment so that they can participate in online school

activities without any distractions or interference. Additionally, it is important to ensure that

the computer or device they use for school is up-to-date, secure, and suitable for their use.

In this case, as suggested by Carretero-Gomez et al., 2021 , training on digital safety should

be available for teachers, school leaders, students and parents.

-

Take care of the mental health of children during and after the distance learning period:

significant behavioral changes have been noted in children due to a forced distance from the

class group and their peers, such as anxiety, restlessness, aggression and sleep or mood

disorders. With remote education, teachers experienced the lack of personal contact and

computer-mediated communication limited their possibility (in terms of times, opportunities, but also knowledge) to explore their students’ wellbeing and needs, and

families were called to manage the impact of the pandemic without any help (Carretero-

Gomez, et al, 2021). Children’s mental health should be carefully monitored and professional

support is desirable in case of psychological distress. Teachers can provide support especially

when children come back to schools setting up activities to help children coping with their

experience (e.g. activities based on reading, storytelling, conversation about emotions).

-

Improve teachers’ pedagogical practices: the pandemic highlighted the need of ensuring

adequate training for teachers at methodological and technological level for integrating ICTs

in the teaching practice. Indeed teachers should have clear knowledge about learning

objectives they are aiming to achieve and identify the precise role that ICT plays in it. Other

aspects that might be improved are promoting collaboration and dialogue among peers and

mastery of learning. In this line, Carretero-Gomez, et al, 2021 suggest also supporting the

development of social and emotional skills by teachers, that appears to be important

especially in remote schooling. Indeed, these skills should help them both to work on

students’ motivation and engagements and to support their own mental well-being.

-

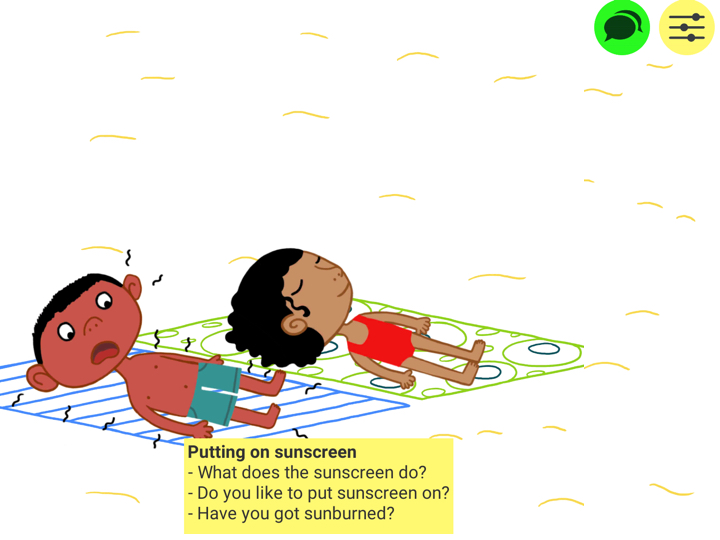

Online session organization: During online lessons, teachers should focus on hands-on and

experiential activities that can help children in this age group better understand concepts

and learn more effectively. It is recommended to organize teleconferencing teaching

sessions with a duration appropriate for the child's age and attention span, and to organize

interactive online learning sessions with teachers and other children of the same age, so that

children can maintain a sense of belonging to their class and learn through interaction and

collaboration. Asynchronous activities to be carried out with the help of parents should be

also designed and made available.

-

Improve the policy in the European Union about ICT: to include Early Childhood Education

and Care in national ICT strategies for education, to provide initial training and ongoing

professional development for all practitioners, to optimize ICT policies by supporting

parental involvement and to support knowledge building and cooperation at all levels for

practitioners, policymakers, and parents

Benigno, V., Caruso, G., Chifari, A., Ferlino, L., Fulantelli, G., Gentile, M., Allegra, M. (2020): Le

famiglie italiane e la didattica a distanza durante l'emergenza: una prima riflessione. Biblioteche Oggi

Trends, Vol 6, N° 2 pp.111-121.

Carretero Gomez, S., Napierala, J., Bessios, A, Mägi, E., Pugacewicz, A., Ranieri, M., Triquet, K.,

Lombaerts, K., Robledo Bottcher, N., Montanari, M., & Gonzalez Vazquez, I. (2021). What did we

learn from schooling practices during the COVID-19 lockdown. Publications Office of the European

Union, Luxembourg,

La Valle I., Lewis J., Crawford C., Paull G., Lloyd E., Ott E., Mann G., Drayton E., Cattoretti G., Hall A.,

& Willis E. (2022). Implications of COVID for Early Childhood Education and Care in England. Centre

for Evidence and Implementation.

UNESCO (2020). Nurturing the Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Children and Young People During

Crises. UNESCO. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373271

Intended Outcomes

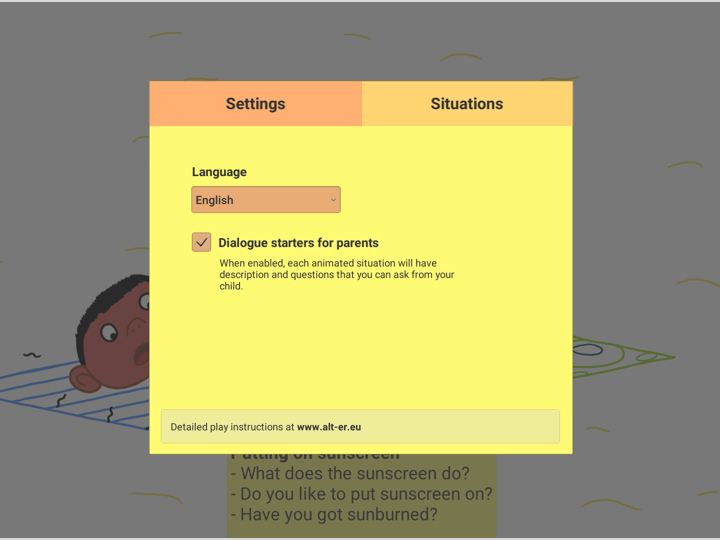

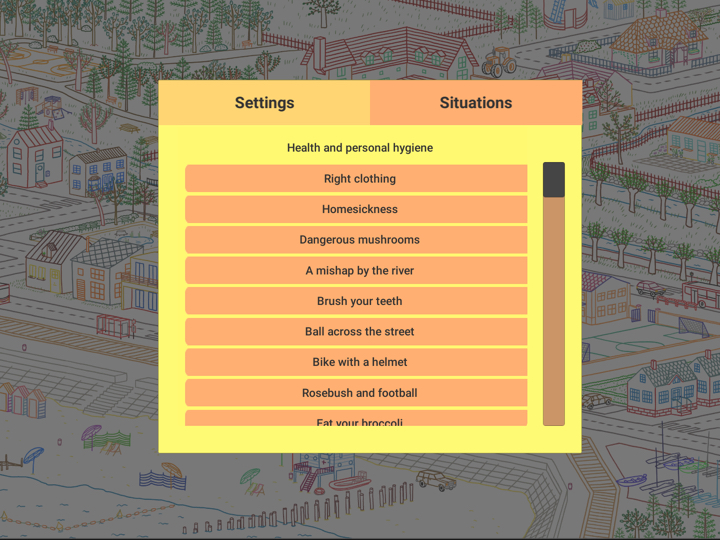

- Creation of a digital Toolbox platform, consisting of existing and/or necessary and internally developed tools and animation activities and for GBL and ECEC contexts. ALT-ER is primarily aimed at teachers for use with students, but can potential have a much wider range of impact.

- Development of a pedagogical framework that embraces creative and innovative learning activities and children’s needs while addressing skepticism, reluctance, and low uptake concerning ICT activities in general and as related to ECEC specifically

- Analysis reports on experiences from the pilot testing and workshop events which highlight the methodology and thinking behind the project further justifying both the framework and activities while generating new knowledge in a highly relevant of European policy

- Publications and interactive platforms for transmission of the knowledge created during ALT-ER project

These combined outputs are thought to be the basis for real change in understanding, appreciation, and practice as regard to benefits and potential of using ICT in ECEC contexts and will create an atmosphere that is hoped will, moving forward, effect EU concerns about early school leavers, enhance performance in education systems, and allow for development of digital competences that will facilitate and improve eventual entry to the labor market.

Project Progress from project manager's perspective

To this point, the project group has investigated the standards and practices in each of the partner countries and are compiling the knowledge into a graphic that will serve to contextualise the accepted processes in each country in order to draw parallels and inform external audiences of the expectations, standards, and practices that exist across the EU.

This has and will continue to provide insight into the areas of development necessary in each partner country, and allow for a scatter plot based on age range and assumed effectiveness of learning activities and goals for the project. This knowledge has and continues to form the basis for the framework we are developing, which will contextualise and justify digital tools for learning as well as prescribing a process for educators to interact with the toolbox that we are curating and creating original elements for.

We have enacted several workshops to this point both in the discovery phase and in further development of a concept that is effective for the deployment of the learning goals we are building based on the preliminary research. Initial concept designs were well received with younger audiences, but were rejected by those in the latter stages of the age band in question as being immature. This led to a reexamination of the issues coming to the forefront, and the best way in which to address them without ostracising any part of the diverse group of intended participants.

Teachers and students on the younger side of the age band very much enjoyed a preliminary concept we were developing that took a train as the main conceit, controlled by the user, and which stopped at activities along the way. As mentioned, this concept proved very popular among groups of younger oriented audiences, but was ultimately rejected by groups representing the older age range in question. Additional research determined that the concept was deemed to be age inappropriate by the older children on the grounds that similar concepts had been a part of their formative experience as toddlers, and were said to be “boring” and intended for younger audiences. Youth respondents referred to a LEGO app that functioned in a similar manner and claimed that was “a game for babies.” This conforms to research provided by multiple partners that young people are far more likely to identify with a concept thought to be slightly beyond their age than one that caters to younger audiences.

Additional testing commenced, and upon regrouping at the second partner meeting, experiences and research led a debate about the best strategy for moving forward. As a result, this train concept was replaced with a hide and seek construct that would be scalable to any age range. Group work has determined that the ease of inclusion of hints, and the manner in which each experience could be augmented and have benefit added by a teacher or parents’ involvement made this a perfect fit for the needs of the project, the target groups, and European students and teachers.

We have engaged with audiences outside the formal partner constellation, mainly represented by schools in each partner country that we have met and worked with to understand the processes they employ as well as their impressions of the activities and goals in development. This has been both a formal and informal process, and has generated both qualitative and quantitative results for consideration in the overall structure of the project and inclusion in the reporting packages. They have responded to questionnaires about the use of technology in their schools and home countries, have opined on the platform and layout of the toolbox design, and have helped crystalize issues that demand attention in the transition phase. Additionally, we have involved several technology and gaming related companies in contextualizing their understanding of the needs of games meant to teach. They have been important for helping the whole team imagine concepts and strategies.

The next phase is to enter final production of the animated assets, and build story worlds with loosely tied narrative guideposts that allow users to create their own story out of the world’s cast of characters and happenings. Students should be able to use the platform as a game based learning tool that is primarily interested in having them “fill in the gaps” and link disparate events through creative, self-reflective storytelling.